Nauru

To its people, a nation. To everyone else, a commodity.

Nauru, an island nation in Micronesia, is home to about 10,000 people, making it the world's third-smallest country by population. I won't pretend to have known much about it before this week, when Nauru emerged in a curious story closer to home.

FTX, the failed crypto exchange, is trying to reclaim money that its founder and former CEO Sam Bankman-Fried channeled into his personal interests. In a new bankruptcy filing, FTX's new court-appointed leadership reveals:

One memo exchanged between Gabriel Bankman-Fried [Sam Bankman-Fried's younger brother] and an officer of the FTX Foundation describes a plan to purchase the sovereign nation of Nauru in order to construct a “bunker / shelter” that would be used for “some event where 50%-99.99% of people die [to] ensure that most EAs [effective altruists] survive” and to develop “sensible regulation around human genetic enhancement, and build a lab there.” The memo further noted that “probably there are other things it’s useful to do with a sovereign country, too.”

Oh, there most certainly are!

The Bankman-Frieds are just the latest foreigners who, over more than two centuries, have viewed Nauru as a haven and cache of resources rather than an independent nation. Its history of colonial extraction is familiar, yet particularly grim. Reviewing the whole narrative puts the FTX Foundation's erstwhile plan to purchase Nauru in its appropriate context.

Pleasant Island

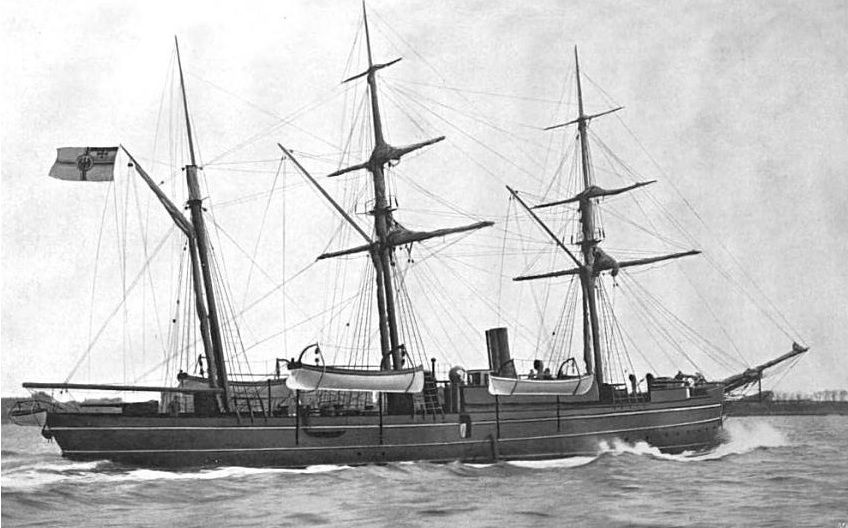

Micronesians lived on Nauru, in isolation from the rest of the world, for three millennia before a British whaler, Snow Hunter, sailed by in 1798. The ship's captain, John Fearn, reported that hundreds of islanders paddled out in canoes, unarmed and "very courteous," holding out bright-green breadfruits as gifts, encouraging the crew to stay. Fearn demurred, but left with a positive impression of the people and the lushness of the land. "No such island being laid down in my charts," he wrote in his trip report, "I presume to name it Pleasant Island."

That would mark the end of pleasantness on Nauru.

More interactions with Europeans, who did eventually come ashore, completely transformed the island's culture throughout the 1800s. Many newcomers had escaped from British penal colonies on nearby islands or deserted other sailing expeditions. Some of these immigrants claimed power through a mix of marriage and violence. They traded food and water on the island for alcohol and guns.

Civil war

Twelve tribes had long lived in relative peace on the island. That was shattered in 1878, when one of the chiefs was shot and killed at a wedding by someone from a rival tribe. Because the population was now armed, a bloody, ten-year civil war ensued. In the middle of the war, a British Navy captain anchored nearby and reported: “An escaped convict is king. All hands constantly drunk: no fruit or vegetables to be obtained, nothing but pigs and coconuts.”

The war ended in 1888 when Germany, seeking to protect its interests around the region, annexed the island. German marines came ashore, arrested all of the chiefs, confiscated their arms, and restored the prior king to rule as a subject of German New Guinea, which held control until 1919. Nauru was now a colony.

Phosphate mining

At the turn of the 20th century, a British prospector came across a beautiful piece of rock in Sydney being used as a doorstop. The rock, which someone had brought back from Nauru, turned out to be phosphate, an important and ingredient for fertilizing crops. The island, they discovered, had formed over the ages by coral reefs filled in with calcified seagull droppings, or guano, which is rich in phosphate. Suddenly, Nauru was not just a strategically located land mass but an incredibly valuable natural resource.

Germany gave the mining rights on Nauru to the Pacific Phosphate Company, which started exporting the mineral in 1908. During World War I, the island was captured by Australian troops, and Nauru became part of the British empire. The League of Nations appointed Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom as trustees of Nauru. Mining rights transferred to the British Phosphate Commission.

National Geographic published an article in 1921 titled, "Nauru, the Richest Island in the South Seas." Though largely positive about the island's future, the piece noted what was happening to the landscape:

A worked-out phosphate field is a dismal, ghastly tract of land, with its thousands of upstanding white coral pinnacles from ten to thirty feet high, its cavernous depths littered with broken coral, abandoned tram tracks, discarded phosphate baskets, and rusted American kerosene tins.

As the land was stripped bare, Nauru suffered other devastations brought upon by foreign mining workers: a flu epidemic killed a fifth of the native population; infant paralysis became common; and Nauruans were in danger of extinction. (Their survival is celebrated to this day as a national holiday.)

World War II

All of that devastation preceded World War II, when Nauru found itself in the middle of the so-called Pacific theater and came under attack by both sides.

Germany bombed Australia's mining operations there. Japan, interested in the phosphate, occupied Nauru and deported the majority of the native population to another island. One boat in the forced migration was torpedoed by the United States. Allied victories in the region helped stop the onslaught, but kept what was left of Nauru and its people isolated until the very end of the war. When Japan surrendered, control of the island was returned to Australia.

The wars continue to haunt Nauru. Last year, the whole country was forced to shut down for several days when a 500-pound bomb dropped by Japan was discovered unexploded and had to be defused.

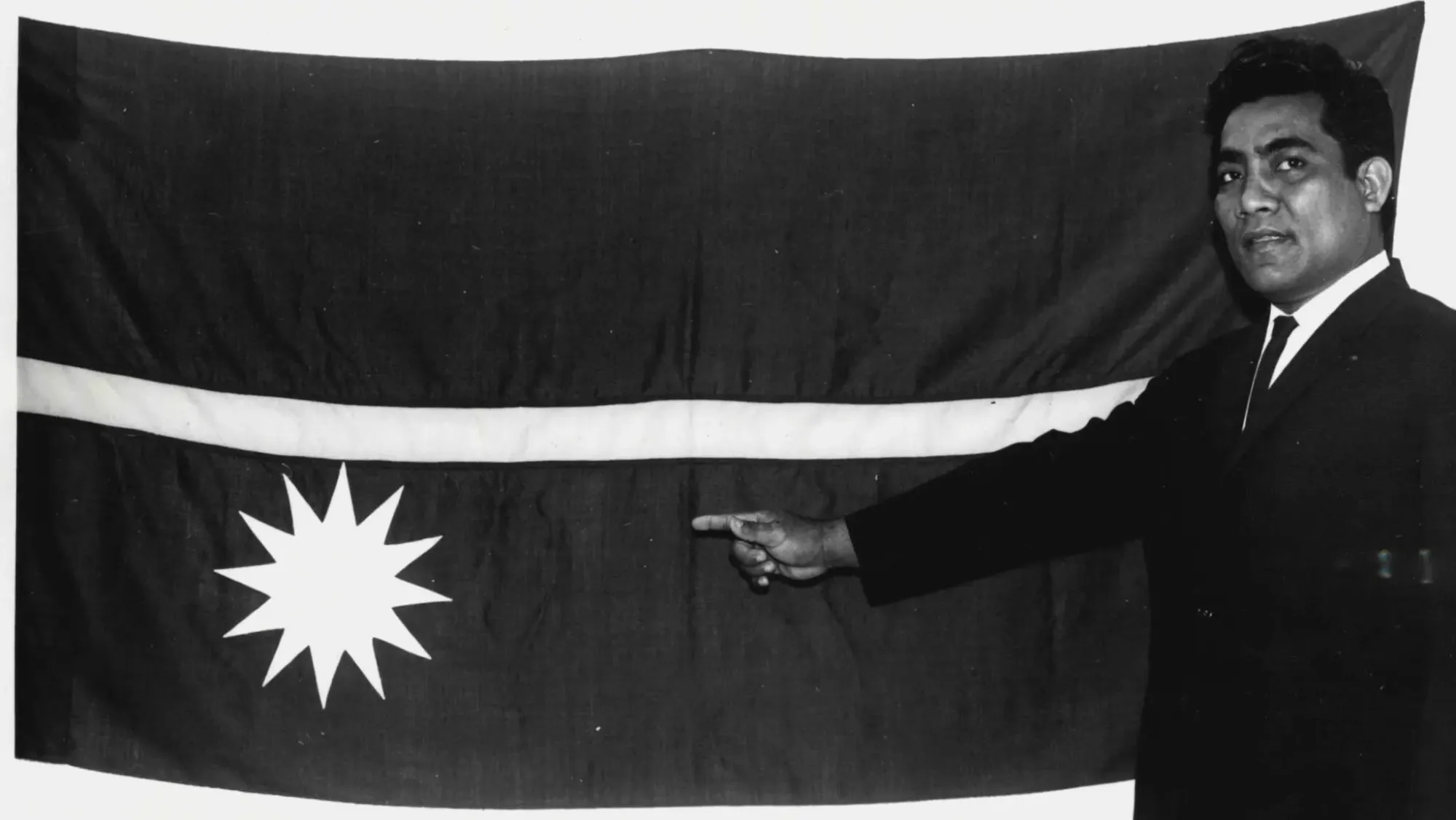

Republic of Nauru

Nauru declared independence in 1968. With its population finally growing again and having taken control of its own mining operations, the country rebounded economically and had, at one point, the world's highest GDP per capita. When the Los Angeles Times visited in 1985, its article began: "Out here, a hundred leagues from nowhere, the world's richest republic is dozing away fat, happy and forgotten under the equatorial sun."

That overlooked the damage already done and the fact that Nauru's phosphorus, while still among the world's purest and most valuable, was destined to run out by the end of the century. By that point, Nauru was bankrupt, and the majority of its land (the whole country is a third the size of Manhattan) uninhabitable. Nearly all of its food is imported and prohibitively expensive for the remaining population.

Most of Nauru's roughly 10,000 people today live on the coastline, which is particularly vulnerable to climate change. Scientists think the remaining livable land will erode within a decade, a similar fate as other Pacific islands like Tuvalu.

Nauru has attempted to spawn other industries and opportunities to save itself: offshore banking for tax evaders; deep-sea mining for other minerals beneath the island; letting Australia detain migrants there under inhumane conditions; selling passports to foreign investors; allying with Russia; etc.

From time to time, somebody floats the idea of purchasing (today's word for annexing) Nauru: maybe the U.S. or a random billionaire. It won't be Sam Bankman-Fried at this point. But his foundation's musings about the idea were just the latest insult to a nation that everyone, aside from its own people, has only been able to see as a commodity to be bought and sold.

Read more from Zach

Sign up to receive occasional emails with new posts.